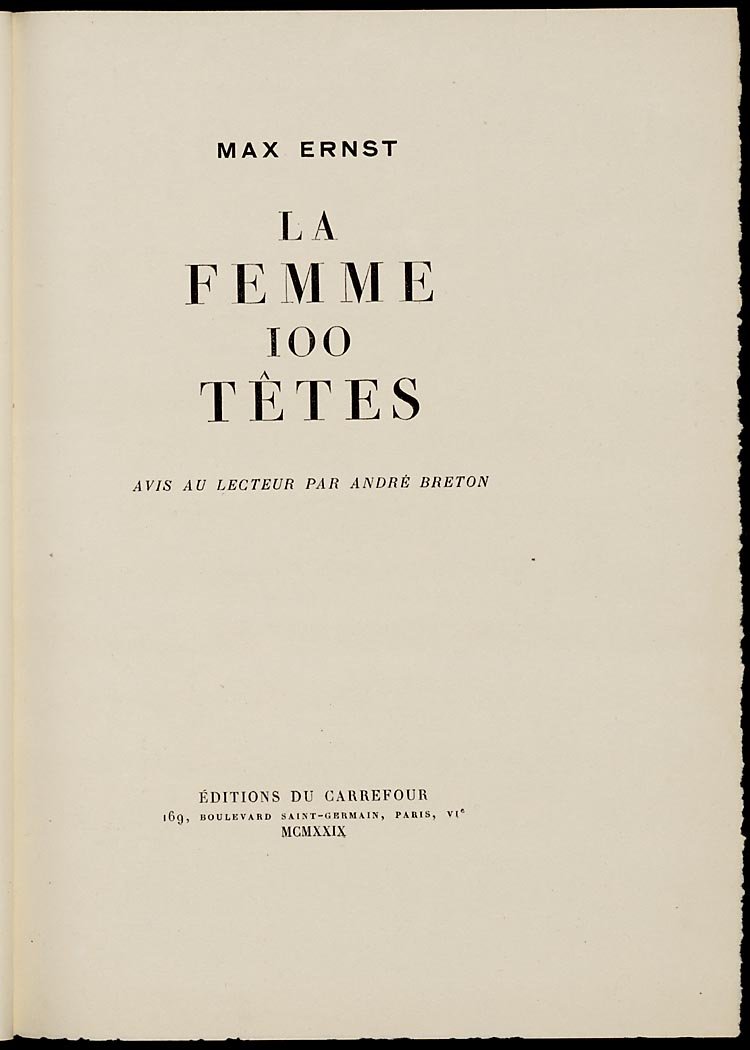

La femme 100 têtes

Year: 1929

Author: Max Ernst (1891 - 1976)

Artist: Max Ernst (1891 - 1976)

Publisher: Éditions du Carrefour

No hierarchy

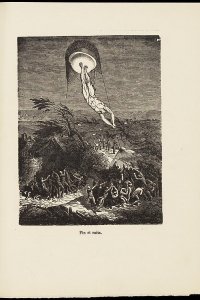

In the collages, dissimilar elements are brought together without forming a logical whole. They are in fact democratized by the collage technique, because none of them dominates the other elements. Without any connections, there is no hierarchy. One element might stand out more than another, or take up a more central position than another, but the distinction between main elements and supporting elements has been lifted: readers can impose their own order on them. The choice of elements was made by Ernst. One of his main goals was obscuring the meaning of the original engraving. That is why he avoided overly familiar engravings like the illustrations of Gustave Doré and William Blake.

Surrealism caused a worldwide shock. Ernst did pioneering work with new techniques that he called Übermalung, frottage, grattage, decalcomania and collage. He used Catholic themes and Freud's explanation of dreams for his iconoclastic and sacrilegious universe. His impact was enormous, also – or perhaps especially – in the humorous genre. American artist Edward Gorey, like so many other artists, owed much to his inventions. The echoes of his collage technique also reverberated throughout the Netherlands for a long time. In 1977 for instance Dutch poet Gerrit Komrij wrote twenty poems for collages by artist J.B. Meinen, published under the title De verschrikking. Rudy Kousbroek published Vincent of het geheim van zijn vaders lichaam in 1981, with illustrations that Ernst could have used in his collages.

La femme 100 têtes was the first collage novel. The title itself is a collage of meanings: The woman a hundred heads as well as The headless woman - and there are more possibilities than '100 têtes', 'sans tête', 's'entête' or 'sang tête'. Nine chapters 'tell' the story of a woman who is believed by some to be Mary. Her name is Wirrwarr, Perturbation and Germinal ('my sister', camping out alone between phantoms and ants). As each page contains a single print with a brief subtitle (the legend), the reader mostly follows the trail of the illustrations. Although they are intentionally confusing, the subtitles are crucial in meaning. In the first chapter for instance, the consecutive collages as a whole appear to reject the dogma of the Virgin Birth. The legends were also published subsequently by Ernst under the title Le poème de la femme 100 têtes (1959). Two other collage novels were published in 1930 and 1934: Rêve d'une petite fille qui voulut entrer au Carmel has a certain narrative progression, and in Une semaine de bonté, the images are derived from eroticism, hysteria, and mysticism.

Meeting

The first two collage novels were published by Carrefour, owned by book seller Pierre Lévy (1894-1945). This young Parisian publisherprinted the Surrealist magazine Bifur from 1929 to 1931, and brought together a number of big names in twentieth-century literature prior to1931: Max Ernst, Henri Michaux, Franz Kafka, James Joyce, William Carlos Williams and Man Ray, for instance. The publisher and artist met in 1926 after an exhibition of Ernst's series of prints 'L'histoire naturelle'.

La femme 100 têtes was published on 20 December 1929. Because its production was expensive and sales were doubtful, only 1000 copies were printed. But it sold quite well, and within a few weeks publisher Carrefour had already sold out its entire supply. Besides the regular edition, 88 copies appeared on Dutch Pannekoek paper. The pictures are printed more clearly in these copies, and have remained in better condition. The copy owned by the Koninklijke Bibliotheek, National Library of the Netherlands is number 51 of these 88 copies, containing an extra supplement (in the back) of a catalogue of the important exhibition of 1921 in Galerie Au Sans Pareil, which was wholly dedicated to Ernst's work at the request of André Breton.

The book was bound by Atelier Alix (Paris) in a simple green leather binding. The Alix family provided bookbinders for generations, including the head of the bookbinding studio of the Bibliothèque nationale de France. His granddaughter Hélène Alix, who also worked there, left the BnF in 1949 to start an independent studio with her husband. In 1959, after the death of her husband Henri Alix, who only lived to be 38 years old, the work at the studio could be continued, and her son Jean-Bernard ultimately also came to work there as a bookbinder. Many of the Alix bindings display abstract patterns, based on quotes from the author and illustrator about the story or the characters in the book. The studio also produced bindings in Art Deco style.

Bibliographical description

Description: La femme 100 têtes / Max Ernst ; avis au lecteur par André Breton. - Paris : Éditions du Carrefour, 1929. - [21] p., [147] bl. pl. : ill. ; 26 cm

Printer: Durand (Chartres)

Edition: 1003 copies

This copy: Number 51 of 88 on Dutch Pannekoek

Bookbinder: Alix (Paris)

Note: With a catalogue of the exhibition Dada Max Ernst, held in Galerie Au Sans Pareil, Paris, 1921

Bibliography: Bénézit 5-164 ; Monod 4310

Shelfmark: KW Koopm K 317

References

- Cornelis de Boer, De droom van de iconoloog brengt collages voort. 's Gravenhage, De Boer, 1995

- Paul van Capelleveen, Sophie Ham, Jordy Joubij, Voices and visions. The Koopman Collection and the Art of the French Book. The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, National Library of the Netherlands; Zwolle, Waanders, 2009

- Paul van Capelleveen, Sophie Ham, Jordy Joubij, Voix et visions. La Collection Koopman et l'Art du Livre français. La Haye, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Bibliothèque nationale des Pays-Bas; Zwolle, Waanders, 2009

- Julien Flety, Dictionnaire des relieurs français ayant exercé de 1800 à nos jours. Paris, Technorama, 1988

- Catherine Lawton-Lévy, Du colportage à l’édition: BIFUR et les Editions du Carrefour, Pierre Lévy, un éditeur au temps des avant-gardes. Genève, Metropolis, 2004

- Max Ernst, Bücher und Grafiken.Stuttgart, Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen, 1986

- Françoise Seince, 'L'atelier Alix ou Le secret de la reliure de qualité',in: Art & métiers du livre, (1995), 193, p. 11-12

![Collage [2] door Max Ernst](/sites/default/files/styles/galerie/public/images/la-femme-100-tetes-collage2.jpg?h=cad2ca3e&itok=bd5JQxor)

![Collage [3] door Max Ernst](/sites/default/files/styles/galerie/public/images/la-femme-100-tetes-collage3.jpg?h=bdeacb1c&itok=PtAzxeA5)